It may be counterintuitive, but data shows that issuers swapping from fixed to floating as rates start rising can save.

Corporates that loaded up on fixed-rate debt during the pandemic but believe that now—as the Fed starts a rate hike cycle—is not the ideal time to swap some of their debt to floating rates may want to think twice.

- That takeaway emerged in a session of the spring meeting of NeuGroup for Capital Markets sponsored by Wells Fargo that featured present value back-testing data for swaps from prior rate hike cycles.

- The data show that, with some exceptions, issuers that did five- or 10-year swaps to floating rates around the time rate hikes began in 1994, 1999, 2004 and 2015 ended up reaping positive net present value savings on an annual basis from those swaps.

Counterintuitive but not illogical. A banker from Wells Fargo presenting the data acknowledged that swapping to floating rates as the Fed raises rates to fight inflation may seem misguided. “It’s a little counterintuitive to think the time to go floating is when the Fed’s just starting off its hiking cycle,” he said.

- “But the rationale here is that markets are forward looking and, often at that time, the market has somewhat correctly predicted what the Fed’s going to do and even overestimated it and given you a margin of safety, which you effectively profit from if you go floating.”

- Another Wells Fargo banker noted the “asymmetry” of how long, on average, rates remained at the trough level during the four rate hike cycles examined—46 months—compared to the average time they remained at peak levels—nine months.

- That underscores that corporates that swapped to floating paid lower rates for longer periods, in part because the Fed has erred on the side of leaving rates lower for longer out of fear of derailing an economic recovery, he said.

- Now, though, the Fed is in a mode where most observers say it is behind the curve, perhaps meaning the market is pricing in a jump in rates that may overshoot the reality, leading to a recession and rate cuts.

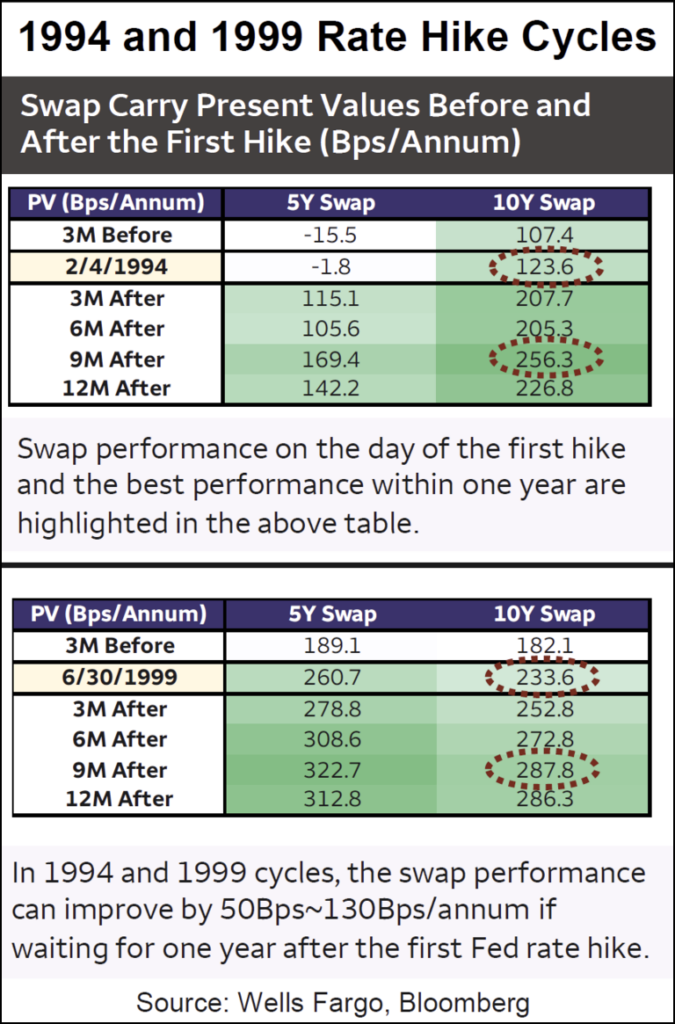

What the data reveals. As the first table below shows, the present value savings realized from swapping to floating in the 1994 rate cycle totaled 123.6 basis points for a 10-year swap executed on the day of the first rate hike; so the rate cycle was priced in on the first day it began. However, an issuer that waited for nine months after the first rate hike would have saved 256.3 basis points.

- Why? The presenter said, “A reasonable theory is that the market thought it had the Fed figured out in ’94; but over the first nine months of hiking, it got scared that the Fed was going to hike even more. The interesting part is the market was right on the first day, so the additional hikes priced in later turned out to be an overreaction—one that someone paying floating thereafter benefited from.”

- He noted that in 1994, five-year swaps done three months before or on the day of the first rate hike did not pay off, with losses of 15.5 and 1.8 basis points, respectively. But waiting for nine months after the first rate hike to swap saved the theoretical issuer 169.4 basis points.

- The savings for a 10-year swap done on the first day of the rate hike cycle in 1999, seen in the second table, totaled 233.6 basis points; that jumped to 287.8 basis points for a 10-year swap executed nine months after the first rate rise.

- In the 2004 and 2015 cycles, the presenter said, “the optimal time to execute got closer to the first rate hike, or even before it.”

- Bottom line: the data demonstrate that issuers in past rate hike cycles that swapped within a year of the first rate hike would have realized savings.

The yield curve question. Wells Fargo also presented data showing that prior periods with flat or inverted yield curves—as is the case now—have been good times to swap to floating rates. For example, in the 1989 and 2000 inversion cycles, the swap performance was the best when executed within the three months of the curve inversion, according to the presentation.

- The problem, members said, is that it’s hard to convince management to swap to floating when there is, initially, no positive carry on the swap.

- “While we all know that initial carry is not an indicator of how well the swap is going to do, it is a lot easier to get your management on board if you tell them that on day one I’m going to start saving 120, 130 basis points, 150 basis points,” one member said.

- For that reason, corporates often layer in their swaps over time, to minimize risk. “We don’t like to take too much exposure on one day. We’re trying to take more bites of the apple over the course of time,” the member said.

- The Wells Fargo presenter acknowledged the challenge facing treasury teams advocating for swaps to floating at times like this. “It is very hard as a corporate to go floating when the curve is inverted, precisely because there is not that immediate carry that is often easy to explain around the organization to drive the decision to go,” he said.

- “And yet economically, I think the rationale behind why these savings are so good is the fact they’re recession predicting. That as much as there aren’t immediate savings, if it’s highly likely a recession follows and/or rates get cut, that’s a great time to be floating. You want to capture as much as that time when you’re at the trough period.”