An update of a story—one of NeuGroup’s most-read articles—about physical and notional cash pooling.

By Susan A. Hillman, Partner, Treasury Alliance Group LLC

Eight months into the global pandemic, liquidity and cash remain top-of-mind for many multinational corporations coping with uncertainty over the shape and timing of economic recovery. That makes this an opportune time to reexamine a critical liquidity management tool that has been around for decades but has always required careful evaluation before implementation: cash pooling.

- Further due diligence is in order now in given tax and regulatory changes in the past few years that may bring more scrutiny of the objectives of a company’s cash pool structure and affect the ability of banks to offer cash pooling services.

Cash pooling defined. Cash pooling is a short-term cash management tool whose objective is to eliminate idle cash and reduce overdrafts among subsidiary operations that have varying daily cash positions. There are two approaches: physical and notional.

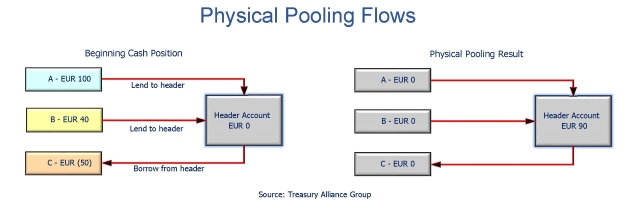

Physical pooling allows funds in separate subaccounts—at the same bank—to be automatically swept to and from a header account. The participating entities’ bank (sub)accounts are either in surplus or deficit position on an end-of-day basis. The physical concentration to the designated header account effectively zero balances the subaccounts. Physical pooling can be used across multiple legal entities, located in the same or different countries—but on a currency by currency basis.

- Movements between accounts are categorized as intercompany loans to and from the header entity and the participating subsidiaries. Specific loan documentation related to the pool structure is prepared in advance. The holding entity should be designated as an agent for the group which allows the interest paid and earned to be treated as bank interest and is not subject to withholding tax.

- The sweeping entries are documented daily through the bank transactions and arm’s length interest is paid or charged either monthly or quarterly. Physical cash pooling is a transparent and efficient liquidity management tool. The documentation and bank transaction detail leaves a sufficient audit trail that is appreciated by corporate tax and would satisfy even a conservative interpretation in a tax audit.

Notional pooling achieves a similar result but is accomplished by creating a shadow or notional position resulting from an aggregate of all the accounts, which can be held in multiple currencies. Interest is paid or charged on the consolidated position. There is no actual movement or commingling of funds.

- The bank (or system) managing the notional pool provides an interest statement reflecting the net offset that is similar to what would have been achieved with physical pooling. As there is no physical movement of money, intercompany loans are not required to account for the offset.

- Notional pooling across multiple currencies requires that these currencies are brought to a common basis (usually EUR or USD) before the pooling and interest offset can take place. In essence, a short-dated swap is executed by the pooling bank. This makes the process more problematic and not as cost effective, as treasury has no control over the rates or the timing of the swaps.

- The multicurrency appeal of notional pooling is somewhat negated due to the complexity arising from the cross- jurisdictional nature of the arrangements and the need to accommodate multiple regulatory regimes. If accounts are maintained across several banks in different countries, there are complications with cutoff times to say nothing of extra transaction costs and bank fees. Due to the opaque nature of the arrangement, it can trigger tax scrutiny.

Tax reform. US tax reform in 2017 meant multinationals had less tax inducement to have profits booked outside the US in a lower tax jurisdiction—a significant disincentive to tax inversion through an offshore location of regional headquarters. Initially, treasurers wondered if tax reform would affect current or planned cash pooling structures.

- The short answer is no, in part because the US Treasury said the new law would not impact short-term arrangements such as physical and notional pooling.

- Cash pooling is an arrangement to facilitate the management of daily working capital fluctuations between related subsidiaries—it is not used to keep large cash profits offshore.

- The entity holding the pool header account is usually an offshore company and this continues to be advisable from both a tax and practical perspective.

- Currency accounts are not used in the US, there are reserve requirements, overdrafts aren’t permitted and interest can only be earned through sweeps—not on current accounts.

- From a time-zone perspective, the subaccounts will be held in other countries, so an end of day concentration is not logistically efficient.

- A US company is not allowed to be a borrower in a cash pooling arrangement.

- Europe remains the ideal geographic location for a pool structure due to access to financial and currency markets. Singapore is often used as an Asian center; Hong Kong’s attractiveness is declining due to uncertainty and Chinese political repression.

Regulatory scrutiny. Initiatives by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) and BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) within the past few years may impact cash pooling. That said, the actual adoption of these pronouncements is undertaken separately by participating countries and their central banks or regulators.

- The OECD’s BEPS (base erosion and profit shifting) initiative addresses tax treaties, transfer pricing and any perceived financial sleight of hand. For treasurers, it means that now is not the time to push the envelope with complicated treasury structures that involve intercompany transactions—particularly with transfer pricing which may come under scrutiny.

- Does this mean cash pooling is threatened? Not really, because it a well-established short-term cash management tool. However, it is important that treasury has good documentation in place, particularly related to the intercompany arrangements created by cash pooling.

- BCBS’s Basel regulations impact banking services and costs. Basel III (2017) addresses the liquidity ratios banks need to meet, so banks are scrutinizing how business is allocated between transaction services and credit.

- Basel IV (2023) will require banks to meet even higher maximum leverage ratios—particularly larger global banks. There will also be more detailed disclosure of reserves and other financial statistics required.

- The Basel conditions will impact certain services that were previously standard and transaction costs will likely increase—this may affect both the availability and costs of cash pooling services, especially for notional pools.

Takeaways. The benefit of cash pooling arises from allowing separate subsidiaries to use internal corporate cash instead of bank borrowing for day-to-day working capital. A few caveats have always been important, but require closer adherence given tax and regulatory updates.

- Pooling is not an arrangement to aggregate excess offshore cash in an attempt to earn a higher rate of return as interest rates are at zero or negative in Europe—and this also may draw scrutiny from regulators.

- Banks must consider liquidity ratio requirements, so concentrating transactional business with the pooling bank is a good idea. Keep in mind that there are only a handful of global banks that offer cash pooling.

- Clear intercompany loan documentation is essential and rates applied must be arm’s length.

- Excess cash should be repatriated—the 2017 tax law makes this more palatable. So it’s important that aggregate pooled balances are not excessively high.

- Long-term deficit cash in offshore subsidiaries should be handled through separate intercompany loans or other funding—not with cash pooling.