The silver lining in the new scrutiny of global transfer pricing is that treasury might finally escape from its cost center box.

The context here is the mess treasury is going to face with tax, cleaning up after the OECD BEPS Actions. The silver lining is that the new scrutiny of global transfer pricing might serve as justification for treasury to become a profit center, or at least set up treasury centers and in-house banks that get better compensated based on arm’s-length pricing for services rendered. Few external banks are offering a treasury services where they don’t earn a profit, unless the services are part of an overall “wallet” that is profitable–so why should an in-house bank not be generating profit when providing treasury services for group affiliates?

The silver lining in the new scrutiny of global transfer pricing is that treasury might finally escape from its cost center box.

(Editor’s Note—Original publication date: March 17, 2015)

The context here is the mess treasury faces with tax, cleaning up after the OECD BEPS Actions. The silver lining is that the new scrutiny of global transfer pricing might serve as justification for treasury to become a profit center, or at least set up treasury centers and in-house banks that get better compensated based on arm’s-length pricing for services rendered. Few external banks are offering a treasury services where they don’t earn a profit, unless the services are part of an overall “wallet” that is profitable–so why should an in-house bank not be generating profit when providing treasury services for group affiliates?

Arm’s length = profit

To say that an arm’s-length price must have a profit margin in it, may be simplifying things a bit, but it helps get to the argument that treasurers should be overseeing profit centers in response to growing scrutiny on transfer pricing. They should make this argument because it helps them with the biggest issue they face: being starved for resources despite the huge value-added role treasury plays, because they have only relatively soft performance metrics to point to (compared to profits) when asked to cut costs.

Here is just one service where arm’s length pricing should generate a profit for treasury:

Centralized exposure management for affiliates. Paragraph 69 of the OECD Discussion Draft on BEPS Actions 8, 9 and 10 (on revisions to Chapter 1 of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines, including risk, recharacterisation and special measures) lays out the logic [bold is our emphasis]:

“Often a MNE group will centralise treasury functions with the result that the implementation of risk mitigation strategies relating to interest rate and currency risks are performed centrally in order to improve efficiency and effectiveness. It may be the case that the operating company reports in accordance with group policy a currency exposure, and the centralised treasury function organises a financial instrument that the operating company enters into. As a result, the centralised function can be seen as providing a service to the operating company, for which it should receive compensation on arm’s length terms. More difficult transfer pricing issues may arise, however, if the financial instrument is entered into by the centralised function or another group company, with the result that the positions are not matched within the same company, although the group position is protected. In such a case, an analysis of the conduct of the parties may suggest that the treasury function is not entering into speculative arrangements on its own account, but is taking steps to hedge the specific exposure of the operating company and has entered into the instrument essentially on behalf of the operating subsidiary. As a consequence the treasury company provides a service…”

Risk is an important component of proposed transfer pricing revisions, since the entity that assumes the risk (as does the entity that receives capital) should have a capability to add value with it (a new take on substance). This gets to transfer pricing rewarding the entity with the capability, not just one contracted to assume risk (or capital). [Note: There will be a public consultation on these transfer pricing matters on March 19-20 at the OECD Conference Centre in Paris.]

Treasury is often the function with the most capability to manage financial risk and thus arm’s-length transfer pricing should reward treasury for the services it provides in managing it, especially when it involves risk transfer between affiliates, but even risk management done on their behalf.

High value vs. low value-adding services

In contrast to high value-adding risk management activities, there are low value-adding services that require arm’s length transfer pricing: Enough to reflect the service rendered, but not so much to shift profits unfairly by charging well in excess of their value add. The discussion draft for BEPS Action 10 (on Proposed Modifications to Chapter VII of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines Related to Low Value-Adding Intra-Group Services) suggests that financial transactions would fall outside the definition of low value-adding services, which may have transfer pricing determined on a more simplified cost-center basis.

However, one comment letter from bMoxie, a boutique Belgian professional services firm specializing in tax and transfer pricing, notes that financial transactions can be wide ranging, and thus not all treasury services would be high value:

“It is unclear what is meant with financial transactions. We tend to strictly define this is as the exchange of (financial) assets, and accordingly not be as broad as the full spectrum of financial services or services that relate to the financial position of companies. Indeed many multinational groups organize their financial services or treasury departments centrally to enable an efficient and effective service to the group members, which may include the execution of financial transactions, but also certain financial services. These services in turn may be fitting or not fitting the definition of low value-adding services. It is not uncommon that group treasury centers also provide auxiliary services that fit the examples of what is provided in paragraph 7.48 – i.e. that are merely of an accounting or administrative nature, and that do entail processing and managing of accounts receivable and account payable. In other words, the scope of a treasury department typically includes investment and funding activities, and may include other financial services that do require the assumption or control of substantial or significant risk, but may very well include services that could be considered low value-adding services, in the view of bMoxie.

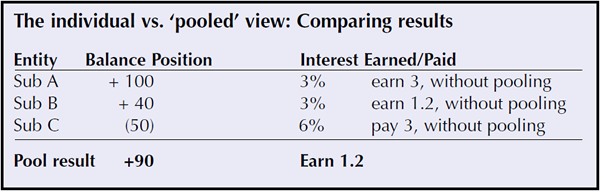

Taking it one step further, even for instance in the light of a cash pool, that entails the exchange of assets, it may well be that the cash pool manager is only to be considered economically to be performing a pure clerical function when it contractually vis-à-vis the cash pool bank and the participants does not assume any risk, however in practice this would not unlikely be the case that the cash pool manager. We just wanted to make the point that even in the light of services auxiliary to financial transactions, there may be a certain division of activities amongst stakeholders that could lead one of the service providers rendering services that could technically qualify as low value-adding services.”

This sort of thinking will not get treasury out of its cost center box. It may also warrant more careful consideration going forward of what activities get put in a treasury center or in-house bank (e.g., payment and collection activities) vs. a shared services center, merely to keep the transfer pricing categorizations clean and the treasury-as-profit-center silver lining intact.