The case for having a programmatic, market-agnostic approach to keep floating-rate debt at a desired level.

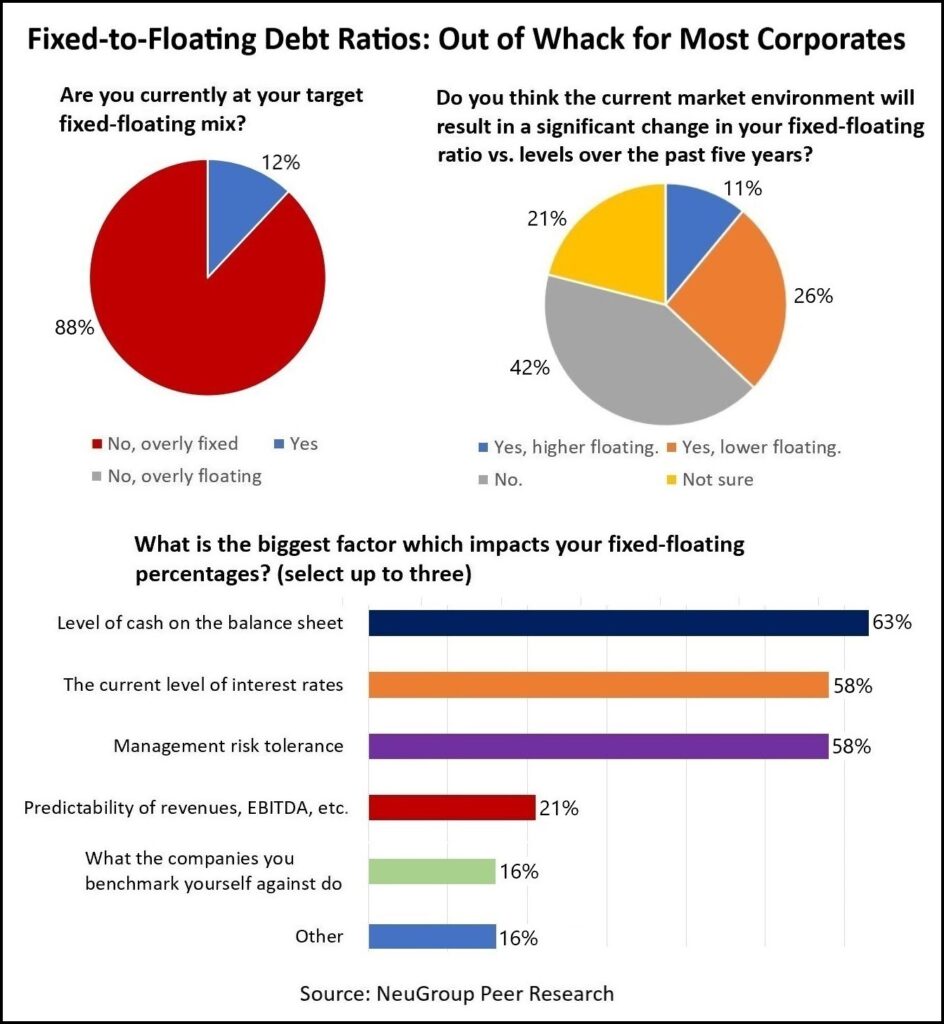

The vast majority (88%) of corporates polled (see below) at a recent NeuGroup for Capital Markets meeting sponsored by Deutsche Bank are above their target percentage of fixed-rate debt relative to floating-rate; but nearly two-thirds (63%) of the companies either don’t plan to make significant changes (42%) to their fixed-to-floating-rate ratio in response to the current market environment, or they aren’t sure about it (21%).

- The poll revealed some context that helps explain this seeming disconnect. Members said that the biggest factors influencing the percentages of fixed- and floating-rate debt are the level of cash on their balance sheets (63%), the risk tolerance of management (58%) and the current level of interest rates (58%).

- The meeting also featured members and Deutsche Bank explaining the value of adopting an internally approved framework to help maintain floating-rate debt at a predetermined ratio to fixed-rate.

Why the fixed-rate cup is overflowing. Many member companies have issued large amounts of fixed-rate debt since the beginning of the pandemic, taking advantage of rock-bottom interest rates, swelling the amount of cash on their balance sheets. And risk-averse senior executives and board members are often not in favor of adding floating-rate debt, or certain types of it, to correct the imbalance, despite the arguments of banks and others that, over time, floating is cheaper than fixed, some members said.

- “We kept our fixed-to float [ratio] where we wanted it through the [commercial paper] markets, but there was always a discussion with the finance committee about the liquidity risk of the CP markets and where long-term rates were,” one member said. “So when the curve got smashed during Covid—and I think almost every corporate has been doing this—with all the [liability management] exercises that you see, everyone’s taking long duration at low rates.

- “And now we’re all catching our breath, and it’s like, now I need to get back to my framework and, what is my new framework?” he asked. “Where do I begin to get back to more of an optimal fixed-float mix?”

The benefits of a framework. Another member explained the basis and benefits of having a framework that determines the ratio of fixed-to-floating. The basis: “We fundamentally believe that floating-rate debt is going to be cheaper than fixed-rate debt over the longer term,” he said.

- That long-term perspective helps address questions about interest-rate volatility that might push against sticking with floating-rate debt, he said. “We believe that there is a decent amount of interest expense volatility that we’re willing to take to be able to lower interest expense over the longer term,” he said.

- The member’s company used an efficient frontier analysis to come up with a framework using a benchmark portfolio that is 40% floating- and 60% fixed-rate debt. “That has done wonders for us, just to make it a programmatic approach and take the decision-making out of it,” he said.

- The framework helps treasury ground the argument to swap back to floating when it may not be obvious that’s the right call from a market perspective. “We report out where we are against our debt portfolio benchmark on a quarterly basis to senior executives, so they generally know if we’re overly fixed or overly floating.You can say, ‘well here we are against the benchmark,’” he said.

- One of the Deutsche Bank bankers underscored the value of frameworks during times like now when there is uncertainty about interest rates and the Fed. “For any of these decisions, anchoring to some belief that you think is sensible and realistic helps you manage the gyrations of the market,” he said. “Because as we’ve seen for the last year and a half and we’ll continue to see, the market has moved materially in interest rates.”

Do the math Before the member’s company adopted the framework, in the wake of the Great Recession and the historically low fixed rates that followed, treasury faced unwavering resistance when it asked for the authority to swap into floating rate debt. “We got to the point where the board said, ‘stop—stop asking,’” he said.

- So in 2017 the member’s team “did the math” and showed the board that if the company had been at a 60%-40% fixed-to-floating ratio during the previous ten years, it would have saved “triple-digit millions.” That helped pave the way for a change in approach.

Talking swap rates. Of course, not every corporate will adopt a framework, making entry points to swap to floating more relevant than for companies that have a programmatic approach.

- One member in this position said, “Since we don’t have programmatic, we are picking entry points and I’m of the opinion that absolute swap rates matter and that they’re too low to be advantageous at the moment.”

- Another member said his team is also looking at the timing of swaps to floating. It did an efficient frontier exercise to help figure out the optimal mix. “We are looking at the term premium, carry, first three years of the swap, is it advantageous to take it now and reassess every year?”

- “Given most corporates are currently underweight floating, it’s important to think big picture and get floating rate exposure back up instead of waiting for the best entry point,” one Deutsche Bank banker said. “Most companies have learned that it is very difficult to time the market perfectly, so the decision to increase floating rate exposure should be both strategic and tactical over the next few years.”